Five buildings and Italo Calvino’s “Six Memos for the Next Millennium” (3, revised)

Exactitude: Zweiter traversiner steg, Viamala, Switzerland

David, the statue that Michelangelo had intended to place on the roof of the Cattedrale di Santa Maria del Fiore finally laid before the Palazzo Vecchio, the then city hall of Florence. David has thereby been revalued not only as a splendid sculpture, but also as a testimony of the era. The work of art is experienced differently depending on where and how it stands; many creators didn’t hide their anxieties and persistence about locating their achievements. This preoccupation often influences even after the creator’s passing. Sir Nicholas Andrew Serota, director of the Tate art museums and galleries, wrote in the media guide for the exhibition of Donald Judd;

… he made very simple decisions about the way in which the spaces were organized and then progressively installed his own works in forms that were satisfying to him, sometimes it took years to get the right combination, and, of course, in making the installation of this show we had about two weeks rather than several years but what we’ve tried to do in the exhibition was to reflect some of the principles that Judd himself adopted in organizing the spaces in the first place and then in the way in which works are installed in particular spaces.

If the location is an indispensable element to involve the work to the artist and the audience, it could be possible to understand what exactitude means in architecture by investigating the relationship between the construction and its site. Since all buildings are designed to fit the place, the necessity must be considered additionally for more accurate comprehension. Conceived by inevitability to answer the specific environmental conditions, responding sufficiently all required purposes, here is a bridge as an excellent example.

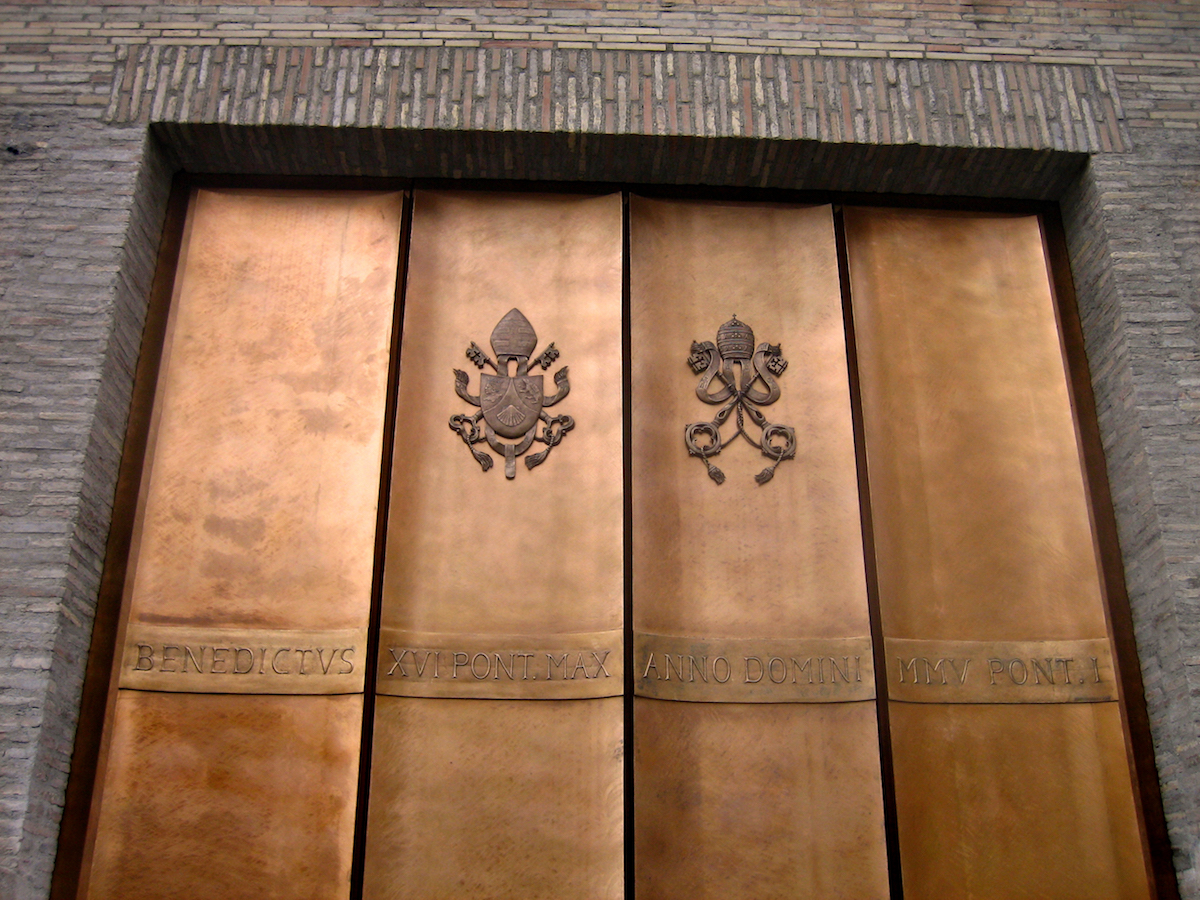

The bridge shouldn’t be described as a mere equipment to function as a tool to cross an obstacle; it also represents the society as other kinds of buildings do. Pontifex Maximus, one of the amassed titles of the Roman emperor since Augustus, the 1st Roman emperor, and thereafter a term of the pope, refers literally to the greatest bridge builder. The bridge here implies a connection to the divinity and a real bridge that spans the river; even in the Middle Ages, the bridge wasn’t what anyone could construct. According to a legend in France, before Saint Bénézet, considered as the founder of the Bridge-Building Brotherhood, built the bridge of Avignon, he had experienced the revelation of God during the eclipse of 1177.

The polysemy of the bridge isn’t found only in the Occident of medieval times. The temple of Bulguksa of the kingdom of Silla, completed in 774 and located in Korea today, includes various evidence. Among the 13 bridges of the temple, certain are shaped as arches and crafted as stairs to climb, leading to the principal buildings such as Daeungjeon (Hall of great enlightenment) and Geungnakjeon (Hall of paradise). This ascending configuration figures the connection from the lower place to the upper area, as from the world to the Elysium, materializing the guidance from ignorance to enlightenment and from mortality to eternity.

Back to the story about exactitude, we will focus on one of the bridges in the valley of Viamala in Rongellen, Switzerland. Its appearance differs from what solid piers across the wide river evoke, merging into the topographical lines in which the bridge itself is hung. The intuition of the structure is glaringly obvious; it offers more natural sensation by holding a swaying wire in hand and stepping on a suspended timber board. Mostly mountainous, in Switzerland, there are numerous pedestrian bridges in this genre; however, two specific reasons summon this one to discuss exactitude.

Firstly, as it is named as the second ([De] zweiter), the other had preceded this one. Unfortunately, the former one in the arch-shaped truss made of thin timber and steel wire had been destroyed by landslides. People consequently have needed to restore; that results in the construction of this second bridge. Demanding by the loss motivates the necessity more than expecting the new one; that makes the current one more likely to be there.

Secondly, the replacing bridge is also conceived by the same creator who had projected the first one, ameliorating its functionality and aesthetic while answering efficiently to other fresh requirements, as Pierre Bonnard retouched his painting already finished and displayed in the museum and as Goya created Maja twice. Interestingly, notwithstanding the precedent somewhat archetypal, the second one includes a richer imagination. That clearly reveals what exactitude points; it materializes the ingenuity with precise calculation and meticulous architecture.

This analogy has the potential risk to fall into the wrong conclusion that more faithful the function is, closer it is to exactitude. To avoid that trap, the bridge of Viamala leaves a key that is ridiculously obvious in the picture, the harmony. Although a building is aesthetically pleasing and functionally flawless, it is important to observe where it sits. If a word is misplaced in a sentence, no matter how conscientious it is, that word shouldn’t be used correctly; even if the phrase is currently spoken and socially understood, the problem persists. The locality of the building concerns the devoted attention and the constant attempt; merely disclosing a situation isn’t sufficient.