Five buildings and Italo Calvino’s “Six Memos for the Next Millennium” (4, revised)

Visibility: Filharmonia im. Mieczysława Karłowicza w Szczecinie, Szczecinie, Poland

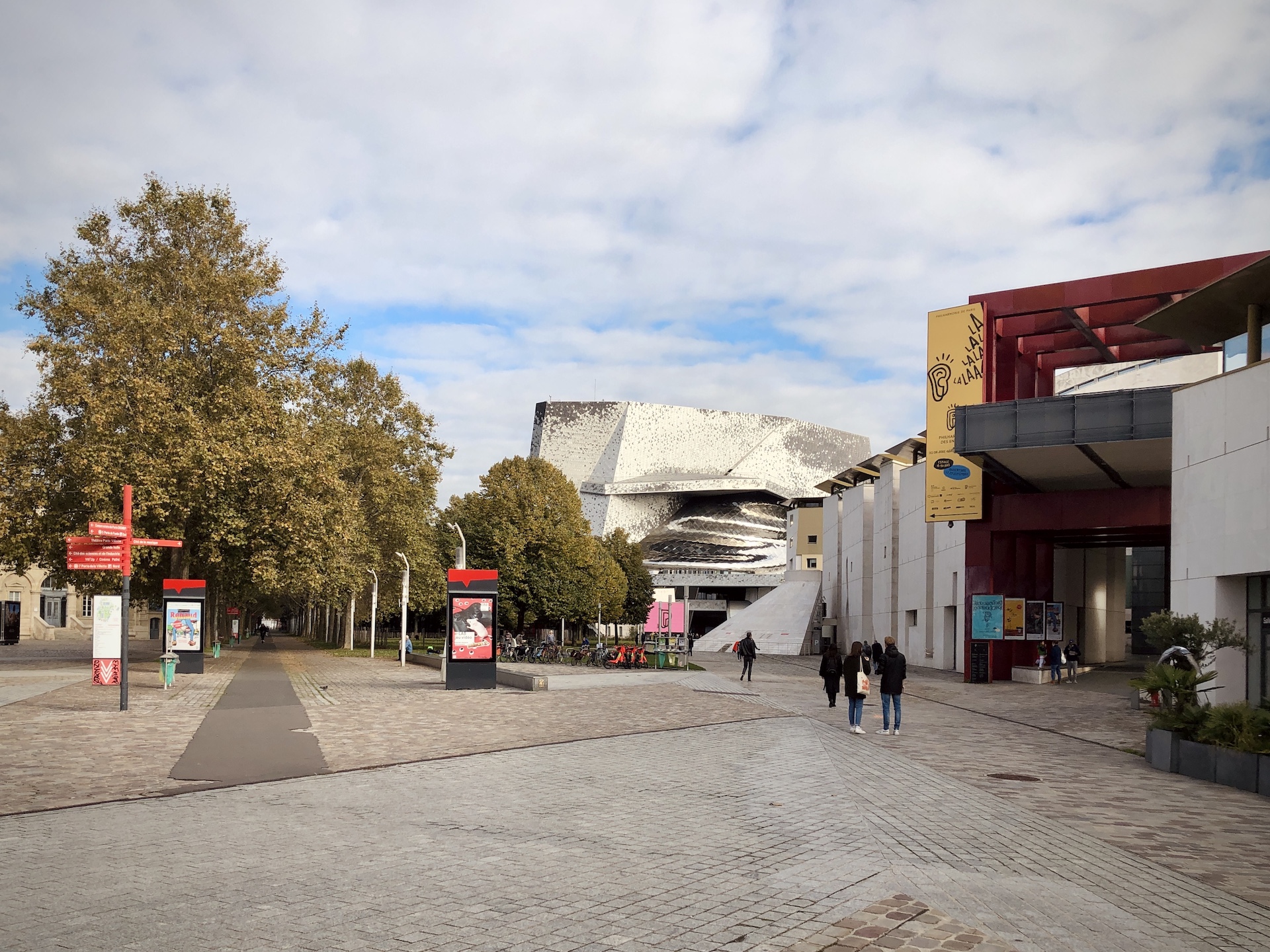

The Philharmonie de Paris has finally opened its doors. Around the project, which costs more than doubled the initial budget, the conflict among the stakeholders has been constantly reported. Obviously, it should be unreasonable to ignore the administrative and political influence for such a large-scale operation; however, disregarding the circumstantial issues, this exceptional edifice could open the path to see what visibility means to the architectural works.

The mass comes in a totally abstract shape; that appears to be somewhat necessary in order to keep the identity within the vivid surroundings of the aligned red pavilions of the Parc de la Vilette and the extravagant former concert hall. Contrary to the splendor, the building itself voices quietly. The enveloping shiny texture resembles the skin of a coiled snake, and the cladding pattern on the walls and the roof glitters like the flying birds; through that luxurious appearance, the signs of the site are barely seen.

An abstract figure often fails to give the first letter of a story. For example, in the house plans of Geoffrey Bawa, the tropical trees are drawn one by one in excessive detail. These are merely a graphical representation of the reality; nevertheless, we could picture the exaggeratedly embowered house in the middle of the rainforest, though we cannot see the entire woodland on the paper. If the plants are strictly symbolized as simple circles, the drawing loses the key of imagination. It should be hard to designate the circles as a thick grove; they only could indicate the technical information such as geographical coordinate and physical dimension.

Including almost nothing in common with other components of the city, dominating the landscape and responding to the context as an absolute presence and as a proper value, this kind of architecture requires more time to constitute the affinity with the surroundings. One day, the matchless superficial personality could be a legacy that inspires other constructions; accumulating various social experiences and planting itself as a node of the relationships, the building could produce the clues.

The Szczecin Philharmonic Hall, which opened at the same time as the Philharmonie de Paris, differs in many ways. Placed on the site of the former concert house destroyed during the war, it sits in the middle of the old town, a vast collection of history, a legacy that the city owns and a source of inspiration to the inhabitants. The effort to build on that site refers ultimately to restore the footprints and to communicate them to the future generations. As a parchment erased and rewritten several times, called a palimpsest, what you see now is clearly different from what it had been, but it includes the past.

At a glance, the contemporary appearance of pure white glass is definitely heterogeneous. The use of disparate material keeps the identity of the building as seen in the Philharmonie de Paris, yet the Szczecin Philharmonic Hall nested and merged into the landscape more comfortably. Agreed with that the Szczecin Philharmonic Hall is significantly smaller than the Philharmonie de Paris, but the site in the old town is far more delicate. The key could be the archetypal symbols that the architects found in the city.

In Szczecin, we discovered this influence of Germanic architecture because this is West Pomerania*. So you can see these massive volumes, these steep roofs in the houses. You can see this verticality in all the main monuments and the churches. And then you have the Philharmonic Hall – something devoted to classical music. So we started to play with how to compose something with elements that could reflect the memory of the site in terms of architecture. And we started to work with this idea of repetition with the volume.**

Made up of multiple similar volumes shifted little by little, with sheer gables on narrow planes, the elevation resembles a part of the old town; people feel familiarity of finding the materialized morphological vestiges. While invisible from the street, the top plays all; several small hoods, each sized as the neighbor’s, clump together to cover a 13,000 m² music venue, instead of a grand structure. It should be underlined that the separation between roof and wall is clearly figured; it is meaningful to the contemporary architecture that is losing the definition of the roof. The building is simplified as a set of contextually sized volumes in a shell of luminous white glass without any abstract shapes; that’s how it fits at ease on that fragile site.

Remembering the painful past with the monochrome devotion in Kolumba of Cologne (Köln), reading an once prospered era on the colored volumes in Bryggen of Bergen and humming the music from the illuminated City Hall of Lyon during the Festival of Lights, people make the buildings a part of life and engrave the inherent traces for other upcoming implantation. Visibility means a clue to imagination; what you see is just a small piece of the story that the architectural works have stored, but it abridges a whole history of the city. It should be the true value of visibility in architecture.

* Pomerania: a historical region on the southern shore of Baltic Sea, split between Germany and Poland

** From Artmania’s interview with Alberto Veiga (https://artsmania.ca/2015/11/17/interview-with-alberto-veiga-barozziveiga/)